Insanabile Scribendi Cacoethes

(The incurable itch to write, independent of having anything to say)

We all know this person on twitter…

Insanabile Scribendi Cacoethes

(The incurable itch to write, independent of having anything to say)

We all know this person on twitter…

Far far away

Out amongst the stars

There’s a planet spinning slowly

We call it ours

Any time, any day

Any moment that we bring to life

Will never fade awayOh, oh the moments come and go

While the memories ebb and flow

Play again, play again

Oh, there’s a hill that we must climb

Climb toward the mist of time

It’s all in here

What we’ve been throughDown, I’m getting it down

Sorting it out

So everything I care about

Is held in here

All of those I love inside

Everybody’s playing for time

You and I still playing for timeThere goes the sun

Back from where it came

The young move to the center

The mom and dad, the frame

Any space, any time

Any moment that we bring to life

Ridiculous, sublimeOh, oh the moments come and go

While the memories ebb and flow

Play again, play again

Oh, there’s a hill that we must climb

Climb toward these mists of time

It’s all in here

What we’ve been throughDown, getting it down

Sorting it out

So everything I care about

Is held in hereAll of those I love

InsideOh, oh-oh-oh-oh-ooh

Oh, oh-oh-oh-oh-oohThe future shines a sunny day

Unpacked memories stored away

All the while the clock keeps ticking

You and I still playing for timeOne by one the voices silenced

For they know that time will tell

It’s time that wears the crown

And time that rings the bellAll cards on the table

All hands are down

Everybody’s playing for time

Everyone’s still playing for timeLooking for a flicker

In the face of the clock

Hidden in the mountain

In the body of the rock

No one seems to notice or to feel the aftershockThey’re all too busy playing for time

Everybody’s playing for time

You and I still playing for time

The ability of humans to have hope is a remarkable thing; we live in a world where probabilities insist on things like suffering, poverty, and tragedy. It is a world where we bicker endlessly from early childhood until old age. And yet we have hope, it is fundamentally human to have that small kernel of belief that tomorrow can be better than today.

I recently read about how AI like ChatGPT hurtles us toward what was predicted by Dead Internet Theory; an online world overrun by content from bots, deep fakes, and click bait. Maggie Appleton describes this dark world eloquently:

“You thought the first page of Google was bunk before? You haven’t seen Google where SEO optimizer bros pump out billions of perfectly coherent but predictably dull informational articles for every longtail keyword combination under the sun.

Marketers, influencers, and growth hackers will set up OpenAI → Zapier

pipelines that auto-publish a relentless and impossibly banal stream of LinkedIn #MotivationMonday posts, “engaging” tweet 🧵 threads, Facebook outrage monologues, and corporate blog posts.

It goes beyond text too: video essays on YouTube, TikTok clips, podcasts, slide decks, and Instagram stories can all be generated by patchworking together ML systems. And then regurgitated for each medium.

We’re about to drown in a sea of pedestrian takes. An explosion of noise that will drown out any signal. Goodbye to finding original human insights or authentic connections under that pile of cruft.”

Maggie Appleton – The Expanding Dark Forest and Generative AI

Although evidence would show that the internet is on a dark path, hope has recently been assembling itself in piles on my desk. This hope comes in the form of books, the type of which remain beyond reach of generative AI or tech bro get rich quick schemes. The more I encounter the soul-less and generic world of content online, the more remarkable and appealing it becomes to spend my time with the type of book that defies categories in an only human kind of way.

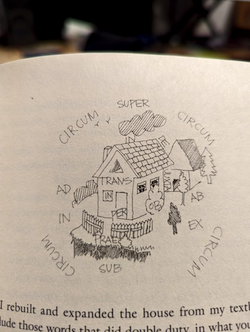

The first book in my small pile is Anne Patty’s Living with a Dead Language: My Romance with Latin. It’s a memoir of her life in retirement and the decision she makes to embark on the journey of learning Latin. I’m drawn to it because of my own journey; I’ve been learning Latin through the adult learning programs offered by Signum University. Beyond the language it’s a book about Ann herself, observations on her own life, and a meditation of what comes after a professional life comes to an end.

The second book is The Long Long Life of Trees by Fiona Stafford. This book crisscrosses the biology of tree species and the world of literature in which trees loom large. It’s not just the prose that makes for novelty, interspersed among the pages are plant illustrations, pictures of paintings, and other miscellaneous artifacts.

I am a reader to be sure, but I’m also a book collector. Although Anne Patty and Fiona Stafford happened to be on my desk as I fretted over the specter of soul-less drivel taking over the web, I would say they are representative of the several hundred books of what I consider my personal library – any member of which maintains the characteristic of being uniquely interesting and utterly human.

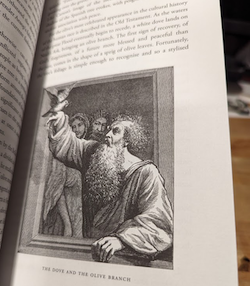

The last book to give me hope is Pippo the Fool written by Tracey Fern but elevated by Pau Estrada’s stylistic illustrations. It is the story of Filippo Brunelleschi, the architect behind the dome of the Florence Cathedral.

Although it wasn’t happenstance that this book would be on my desk – I ordered it recently – it was a purchase motivated in large part by a scheme I saw online to write a children’s book in an hour with ChatGPT. Upon learning of the scheme I thought of the many books I’d read to my own kids, of the memorable ones, and of the craft authors like Fern use to turn things that are complicated – art, architecture, the human psyche – into something intuitive and appealing to kids. The book is well researched, funny, and paced to accommodate suspense as it reveals how Brunelleschi resolved a true architectural miracle.

Each of these precious books is a part of my hope – the thing with feathers – that the act of human expression cannot be supplanted. We have nuances that cannot be mimicked. Our neuroticisms cannot be emulated, only edited. The contradictions and uncertainties we carry and compound over our lifetimes are beautiful and irreducible complexity.

As the web grows darker with generic, machine-generated content, we will always have books and libraries. It conjures, for me, the contrast of a jungle with that of a garden. Gardens need not be overwrought or meticulous. They exist by human intent and, with effort, reflect the beauty of their gardener.

From Paul Graham’s latest essay, “The Need to Read“:

… writing is not just a way to convey ideas, but also a way to have them.

A good writer doesn’t just think, and then write down what he thought, as a sort of transcript. A good writer will almost always discover new things in the process of writing. And there is, as far as I know, no substitute for this kind of discovery. Talking about your ideas with other people is a good way to develop them. But even after doing this, you’ll find you still discover new things when you sit down to write. There is a kind of thinking that can only be done by writing.

I haven’t been writing and it shows in my thinking; short, fitful, and halting attempts to grapple with ideas.

While I have struggled with the momentum of putting thoughts into words, I have been enjoying the long form writing on offer at Substack. It’s a stretch goal but as I try to get going again, I’d love to be a part of that ecosystem. Substack feels like an anti-twitter; the content is long form, well thought out, and focused. These qualities permeate the disparate interests I’m drawn to – whether I’m reading Common Sense, Declarative Statements, or Huddle Up, it’s the sort of writing that you can fill up a coffee cup and sit back and enjoy.

For the moment, however, the goal will be small. To write, to think – again.

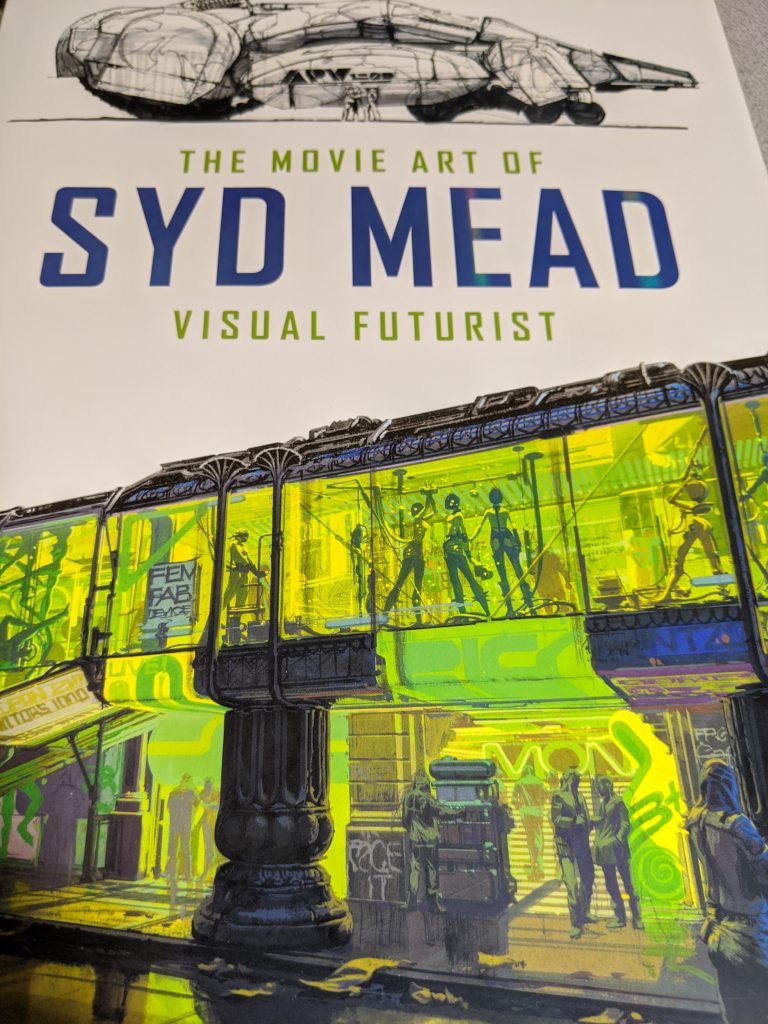

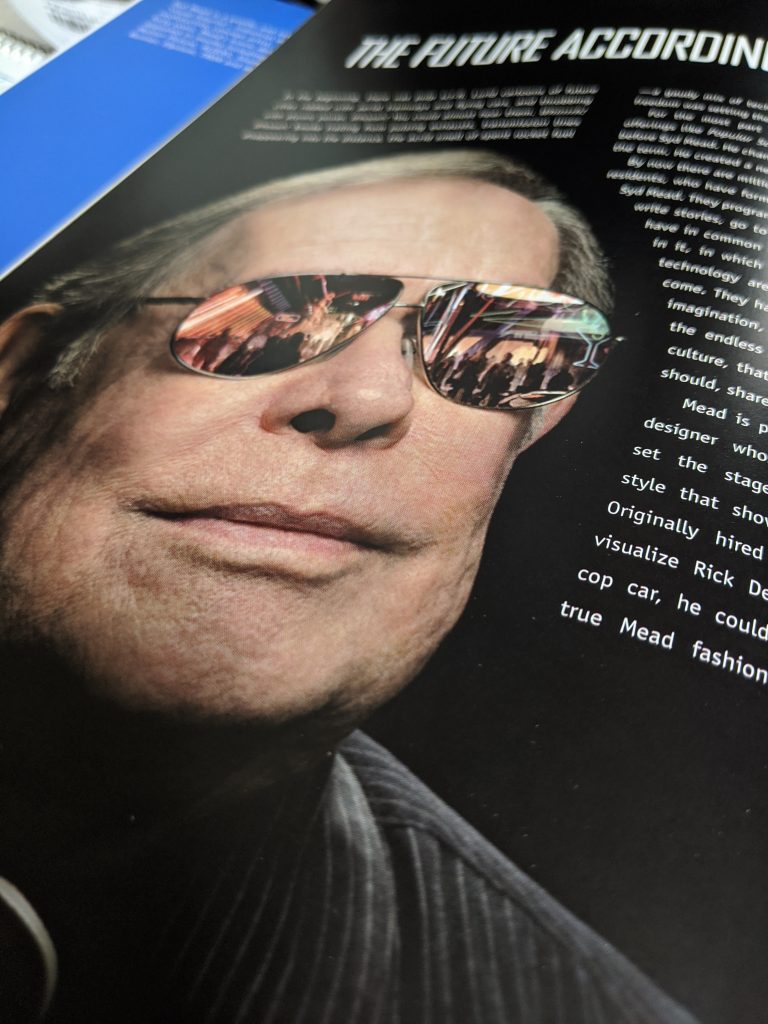

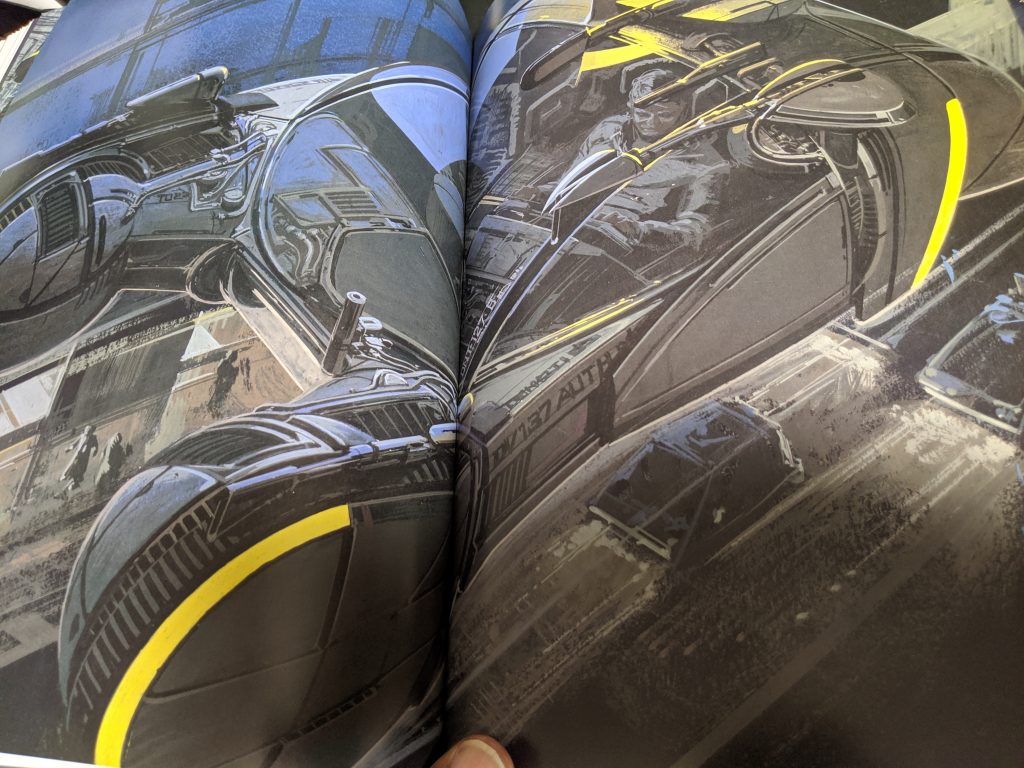

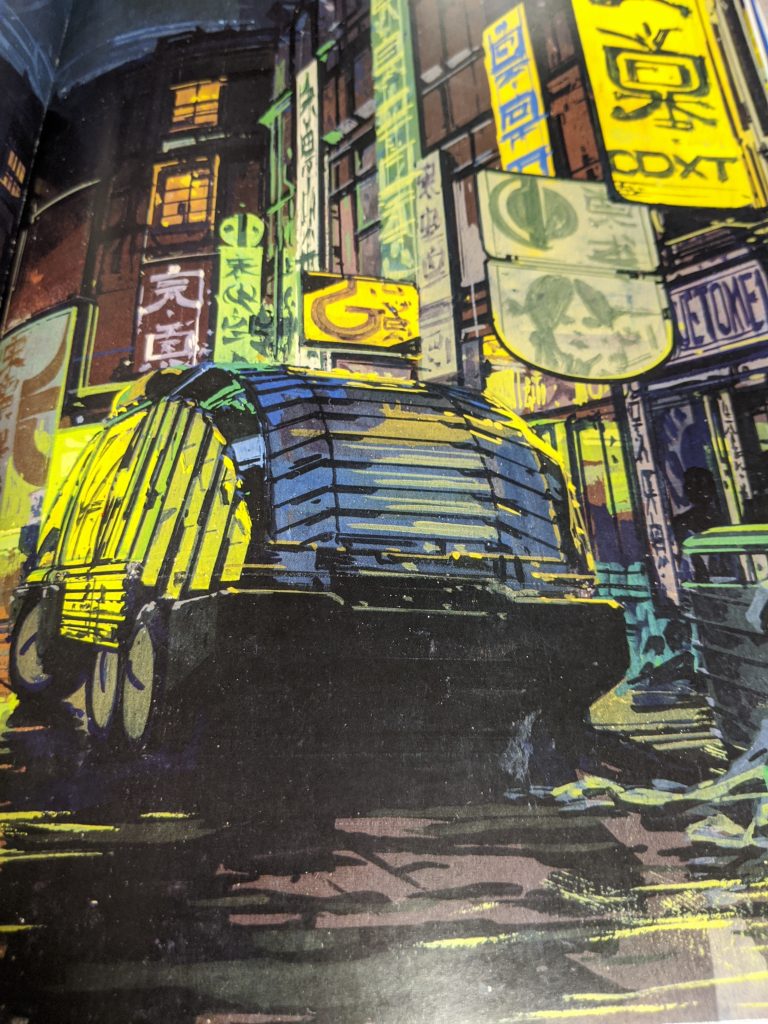

Visual Futurist Syd Mead passed away early this year. I’ve been a long time admirer of his since making the connection of his work and the sci-fi masterpiece Blade Runner.

When I was young I used to draw spacecraft and futuristic spaceports imagining an exciting world of the future. Little did I know there were people who actually did this for a living and I was, in my own amateurish way, trying to be Syd Mead. It was no different than when I’d shoot hoops in the driveway pretending to be Michael Jordan.

I’m fortunate to own a copy of The Movie Art of Syd Mead Visual Futurist and since his death I’ve spent a lot of time looking through his work.

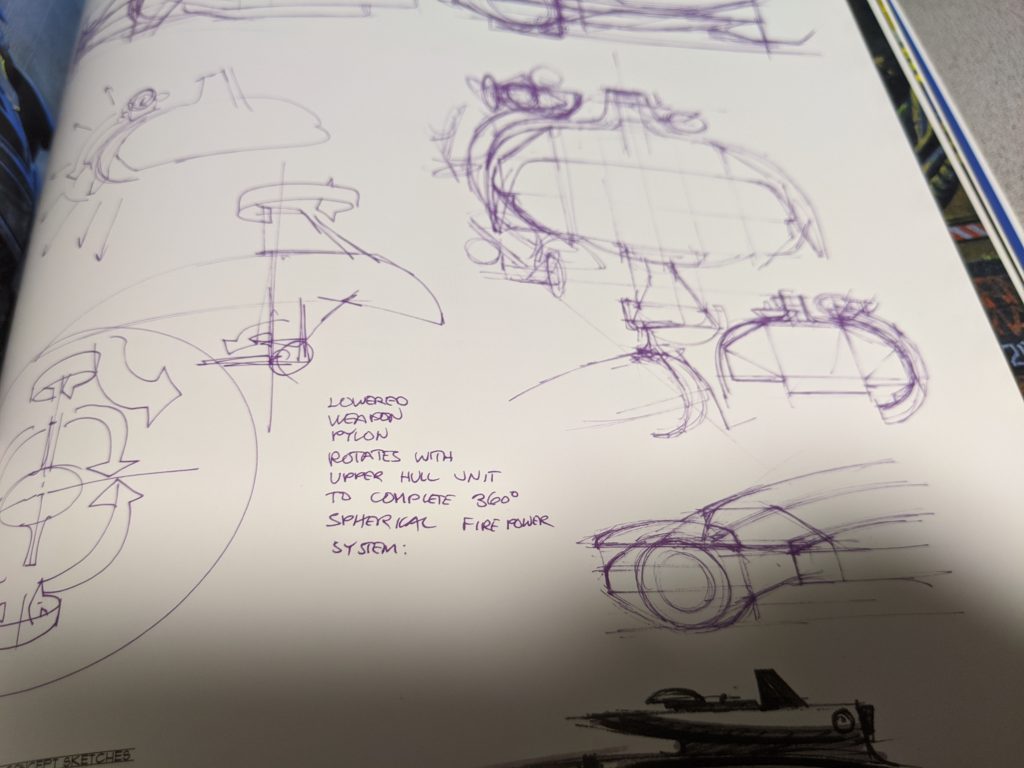

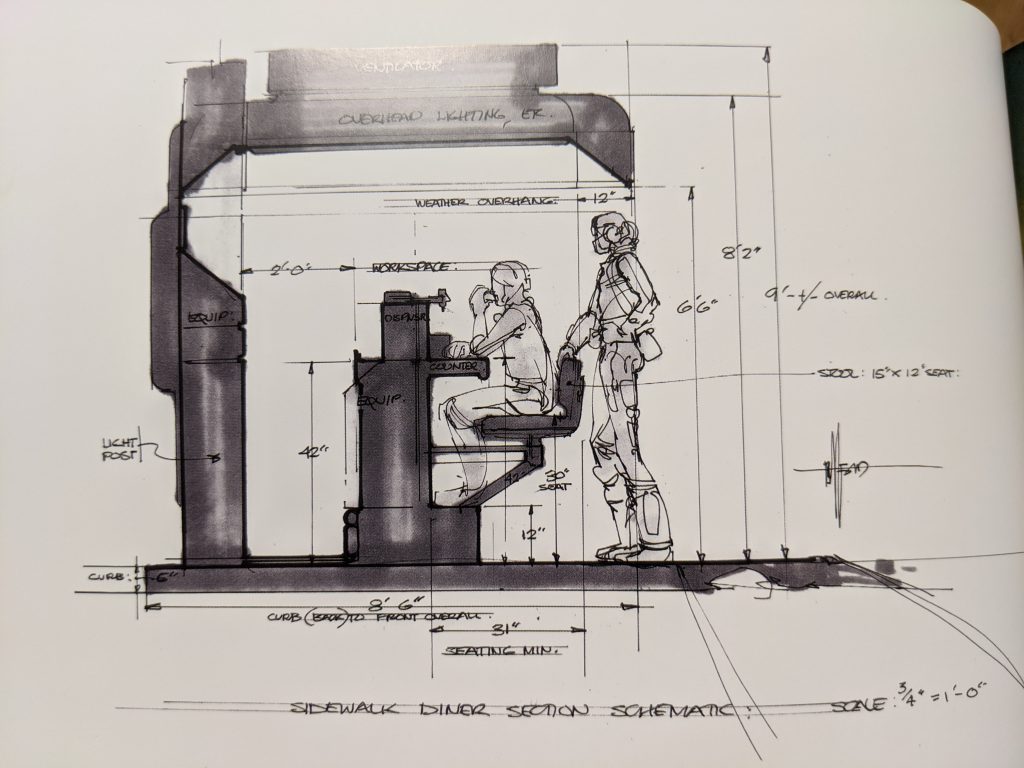

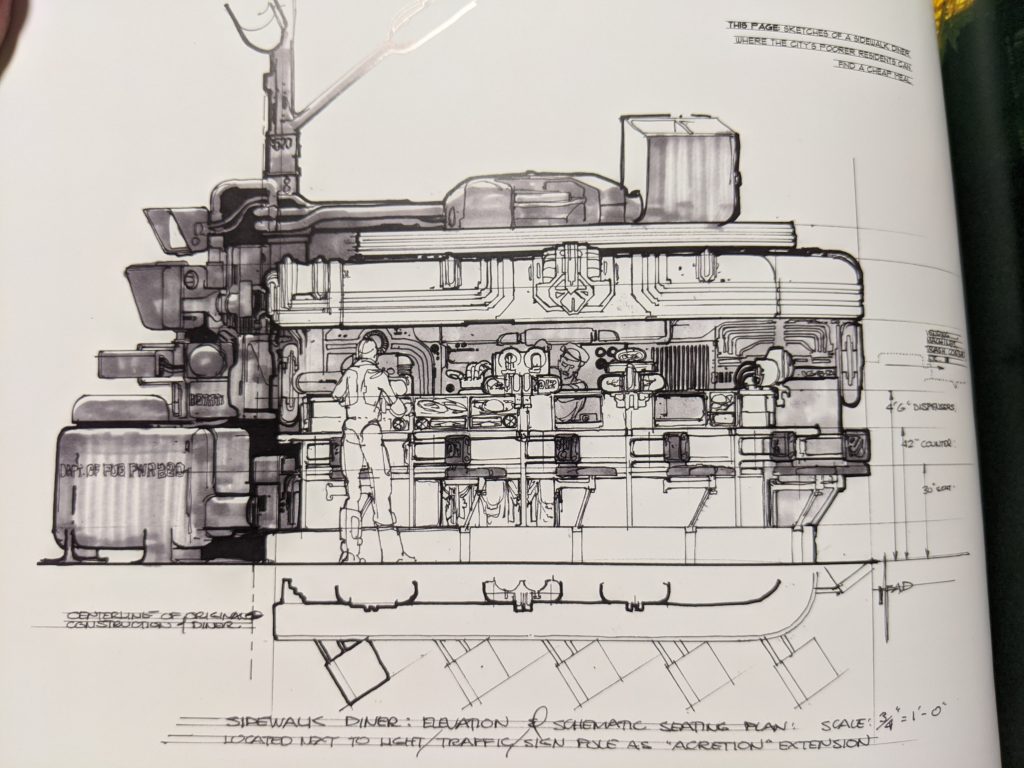

There is a lot of polish to the final concepts but one thing I love about this book is the focus on how he would sketch his way into the final ideas.

His process was not of dealing with futuristic ideas in isolation; when he imagined the future it was a totality – an entire world. In interviews he describes coming to his ideas not just as a matter of “concept” but one of problem solving… thinking about the future and how it might take shape in the face of the conditions and circumstances of arrival.

This sort of design thinking requires detail: measurements, proportions, materials… many other things into which Syd wove his final ideas and renderings.

During his life he worked on many projects – it would be difficult for anyone to have missed his influence. Blade Runner still tops my list (with Aliens as a close second) but there are so many others. I leave off with a short documentary on his life.

Sadly this content emanates from a series of tweets. Although it has been unrolled, I’m adding a redundant backup here.

Brian Kopelmann on becoming a writer:

1) No teacher ever singled me out and told me I should consider a career as a writer. Come to think of it, no fellow student ever did either.

Brian Kopelmann, twitter thread.

2) I was also a late reader. I had a big verbal vocabulary. A gift for remembering/using words. But I didn’t really become a reader until the summer after 4th grade. My mom gave me the book Tales Of A Fourth Grade Nothing. I stayed up all night to read it. Then read all summer.

3) Eventually, I taught myself to read very quickly. I didn’t develop some kind of technique, but I learned a kind of hyper focus–the entire world would disappear when I read which allowed me to read fast and comprehend a great deal.

4) Still, I struggled, badly, in school. If a subject was boring to me, I wouldn’t do the work in the class. Couldn’t, really, so, instead, I would read novels during class, hiding them behind the book I was supposed to be dealing with.

5) I acted in high school plays and assistant directed, but again, not once did a teacher or fellow student suggest I should try and make a career as a performer or writer or creator in the arts.

6) And, although I always felt great kinship with artists, I didn’t think I could be an artist either. I always thought artists were predetermined, special, picked out ahead of time, anointed.

7) Now, I don’t want to lie or be falsely humble: I knew I was a smart person, or smart enough, and I knew I had a way with words–that is, I could write an essay or paragraph and do it in a memorable, easy to read way.

8) But I truly thought that I didn’t have the stuff really creative people had. And I was, secretly, a perfectionist. So if I couldn’t spin gold right away when I tried to write something, I wasn’t able to finish it.

9) This inability to finish work, this giving up, this quitting, felt like suicide to me. Led to self hatred. Even as I found success professionally, in a related field, but not as an artist, I would sometimes try to write, and then quickly give up.

10) And then, months later, would wake up in the middle of the night, try again, delete it, throw it out, wake up hating myself. But somewhere in there, my wife, Amy, told me she knew I was a writer. That I should try it. That I deserved to try it.

11) Soon after that, our first child was born. Looking at him, I knew I didn’t want to be the kind of father who would lie, who would tell him he could be anything he wanted as long as he tried, if I, myself, hadn’t tried to live it, too.

12) And I realized that being blocked led to something dying in me. And that like any other kind of death, this death would be toxic, and the toxicity, the bitterness would leach out of me onto those I loved. I didn’t want that to happen.

13) And so, finally, my best friend @Davidlevien gave me Julia Cameron’s book, The Artist’s Way, and I found myself in it. I found what to call my fear and inability to work. And I started doing morning pages, each day. These pages unlocked and unblocked me.

14) They gave me a ritual, a beginning of the creative day, a way to get beyond perfectionism. They made me realize that no one can anoint you as an artist. You have to do the work, each day, and then, maybe, you just become one. By doing.

15) Shortly thereafter, I stumbled into a poker club, called Levien, told him there was a movie we should write. And that became Rounders. I tell you this because I see from the questions/ comments you ask that many of you are as scared as I was.

16) And I want you to know that you are smart enough. That the teachers didn’t know. That the echoes of their voices don’t matter. And that if you show up each day to do the work, you won’t need anyone else to tell you anything. You will just be, by virtue of doing, an artist.

17) (I understand the ways in which it was easier for me than for most. I was raised with money. I was a white man at a time when that gave me a huge leg up. I had no college debt. I made money young. But none of that stops you from doing. It just made it easier for me).

These photos spark a rabbit hole of thoughts and emotion.

“The struggle of good against evil feels less like a cosmic battle than a longstanding sports rivalry between teams whose glory days are receding. The head coaches come and go, the uniforms are redesigned, certain key players are the subjects of trade rumors, and the fans keep showing up.”

A.O. Scott on The Rise of Skywalker

“…we perfect, most dangerously, our children. Let me tell you what we think about children. They’re hardwired for struggle when they get here. And when you hold those perfect little babies in your hand, our job is not to say, “Look at her, she’s perfect. My job is just to keep her perfect — make sure she makes the tennis team by fifth grade and Yale by seventh.” That’s not our job. Our job is to look and say, “You know what? You’re imperfect, and you’re wired for struggle, but you are worthy of love and belonging.” That’s our job.”

– Brené Brown